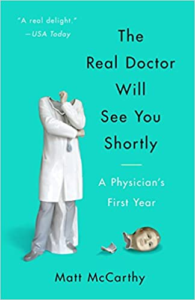

Check out the full notes for “The Real Doctor Will See You Shortly” by Matt McCarthy

What’s the last hard decision you made?

Could someone have died?

Reading through Matt McCarthy’s “The Real Doctor Will See You Shortly” reminded me just how unimportant a lot of the things I do day to day are.

Choosing a video thumbnail and writing a description doesn’t seem that important.

On one hand, it can be discouraging thinking you aren’t impacting people much compared to a doctor saving lives. On the other hand, it can be freeing knowing that you don’t need to make literal life and death decisions night in and night out.

This book made me think of how there are a lot of similarities between jobs in seemingly completely unrelated fields. McCarthy describes presentations about patients that you have to give.

“Your presentations are weak,” he said. “Pick it up.” A wave of relief. “I’ve sensed that.” “Here’s the key,” he said, glancing at his pager. “You’ve only got a few minutes before we lose interest. Every word has to count.”

That’s something to keep in mind whether you’re presenting about a patient to other doctors, you’re a designer pitching a solution to the rest of your team, or giving a talk at a conference. You have a limited amount of time. Your audience has an even more limited amount of interest. Make it count.

“Your presentation has to be problem-based,” he went on. “Why is the person in the unit and what are the barriers to leaving?”

I’m browsing my highlights from this book in a spreadsheet right now. Without context of knowing what book these came from, some of these could just be from books about copywriting that I read too many of. (And don’t apply enough of.)

It’s classic storytelling. If you’re writing a sales letter, you present the problem someone reading might have. You explain the details of that problem and then explain the benefits.

If you’re presenting a patient’s story, you explain who the person (beginning), you explain the problem that’s landed them in the hospital (middle hook), and hopefully you work toward a solution (ending payoff).

But, of course, not everything in a job connects to other jobs. What’s your fluid? During a medical internship, you eventually find out.

A day earlier, I’d spent hours lancing every one of his abscesses with a small scalpel and even more time scooping up the pus with gauze. In college, even in medical school, the sight and smell of those abscesses would’ve made me nauseated, but not anymore. I had been told that every doctor eventually discovers which bodily fluid he or she finds most disturbing, and this realization helps guide the choice of a subspecialty. I didn’t mind blood, spit, piss, or pus. I did mind diarrhea, which meant I wasn’t destined to become a gastroenterologist.

There were moments while reading when I thought, “Wow it’d be great to have this kind of direct impact on people.” Then there were moments where I thought, “Wow it’s great I get to stay at this desk.”

Throughout the book, McCarthy talks about his humanity. In particular, hoping that he doesn’t lose it. He never wants to be someone that’s able to just move on to the next thing after seeing something insane happen in the hospital.

The page-turning moments in the book often involve descriptions of medical procedures, but captured from his perspective. You get a sense of his confusion and apprehension and then see it turn as he gains his composure and the studying and drilling kicks in.

I’ve worked in software and seen how the most effective people are the best communicators. You need rep after rep to build the soft skills. This book often reminded me that communication is probably the biggest career multiplier in other fields as well.

In product design, the goal is often to take something technically complicated and explain it to a lay audience. You choose just how simple to make it. The same happens in medicine.

Medicine is complicated and it is a skill to simplify things in a way that doesn’t oversimplify, to accurately convey in plainspoken language what is actually happening inside another person’s body. I made a conscious effort to do it, so it was irritating to see others doctors use medical jargon with families. Just talk like a normal person, I wanted to say. Pretend you’re not a doctor. But for some, that simply wasn’t possible.

I bought “The Real Doctor Will See You Shortly” after seeing it in a BookBub email. Last year I decided I’d be deliberate about choosing to read outside of my usual interests. I did that for a few months but strayed back to the usual self-development and business books.

It was a great reminder of why I wanted to read outside of my comfort zone in the first place. It’s made me more appreciative of what doctors do day to day. There’s too much to know, too many difficult decisions to get them right every time, and many different ways to simplify things:

The truth is that complex decisions are often made using simple mnemonics. Linguistic shorthand wasn’t encouraged at Harvard—information needed to be mastered before it could be abbreviated—but Ashley had just simplified a series of baffling medical school lectures on dialysis into a mouthful of vowels.

Go check it out if you’ve ever wanted some sense of what it might be like going through a medical internship. Or if you just enjoy stories where the student slowly becomes the teacher. You’ll probably find a lot of interesting connections between something you do and something a doctor does.

For a few moments you get a glimpse at how it really is just another job. Then a few pages later you’ll read a description of cracked ribs and a heart exposed to open air and realize that it really isn’t just another job at all.