I’ve been getting back into the swing of things when listening to podcasts.

Jason & Lauren Pak started their Reasonably Fit podcast. I’ve been following them on Instagram (@jasonandlaurenpak) for a bit now and enjoy their, well, reasonable approach in a sea of fitness influencers. (I’m also a fan of the opposite end of the spectrum with people that look like G.I. Joe characters.)

Main takeaway after binging on a few episodes: “It depends” is the only thing that always applies.

People’s perspectives on fitness and nutrition get shaped very very early in life. Media portrayals skew things. Social media takes those skewed things and layer an illusion that they’re achievable.

I know I won’t look like The Rock but mayyyyybe I can look like this dude on IG…

Jason & Lauren understand different triggers and are very deliberate about how they spread their message. They rarely do before/after shots of clients, because someone’s “after” win should not be lowered because it’s someone else’s “before”.

Anyway, I mentioned earlier this month that I’m trying to shift my information diet away from financial things and more toward health things. Reasonably Fit is definitely a step in the right direction.

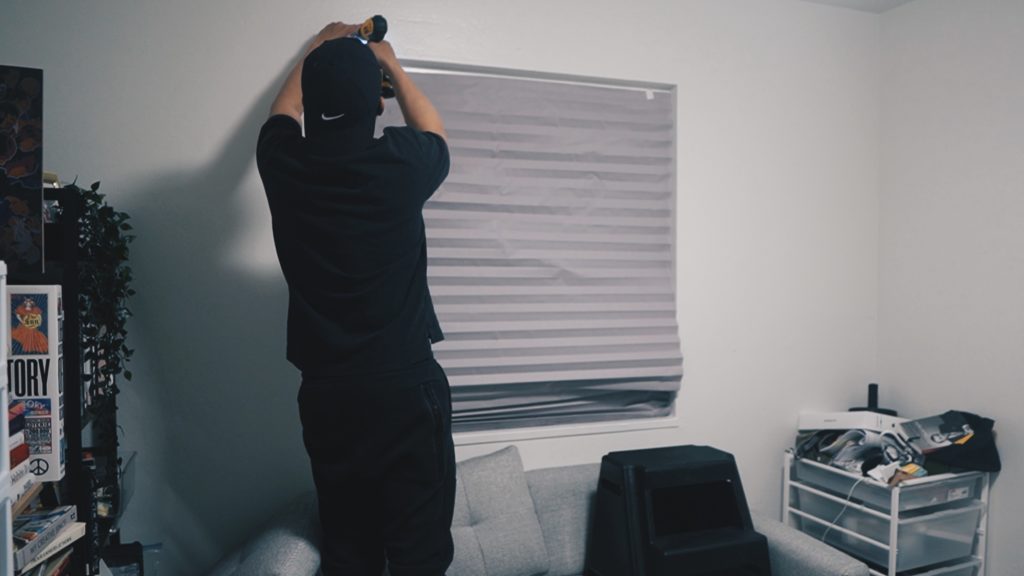

As for the photo in the header of this post, I got a Rogue Jammer pull-up bar to go above the door. The theme this month has been trips to Home Depot, and another one is due tomorrow because I didn’t have the proper socket for my drill to put the bar into the wall.

Chin-ups coming soon…